I’ve found myself unemployed with a bit more free time than usual for the last few months, and I decided that it was

the perfect opportunity to learn a bit about LLM tool use and to try out this whole “vibe coding”

thing.

Inspired in part by one blog post by Thomas Ptacek saying I was nuts not to use LLMs more

and another by Thorsten Ball explaining the nuts and bolts of “agents”

, I set out to make one with

the right ergonomics and features just for me - a CLI application I could run in tmux beside my NeoVim pane while

editing code.

For the impatient, here’s the GitHub repository link: https://github.com/cneill/smoke

Why build my own? #

One of my goals for this project was to implement it without ever using or referencing other popular agentic coding

assistant tools like Claude Code, Codex, opencode, etc. To this day, I’ve never installed any of these tools, and I’m

excited to play with them now that I’m releasing v0.0.1 of smoke. I wanted to implement the basic functionality and

then just see where my exploration took me. It’s quite fun to have a piece of code you wrote start modifying itself

based on your natural language instructions, and you really don’t need to implement a lot before that’s possible.

Given that even the most terminally-online AI hypebois have only had access to these tools for about a year now, my sense was that there couldn’t possibly be a massive moat around any of the existing ones. I also listened to several podcasts with Dax and Adam (the guys behind opencode ) discussing their experience implementing one of these tools and engaging in The Discourse around them. It sounded like there was a lot of copying going on between different tools, and while I didn’t think I’d make anything revolutionary by doing it myself, I wanted to see what I’d come up with given my own preferences, a totally blank slate, and no expectations. I don’t mean to denigrate the other tools - I’m absolutely certain that they are way more capable than my own. But nothing beats a home-cooked meal.

What’s an agent? #

For those who have never used one of these CLI-based coding assistants, the basic premise is simple: first, build an LLM chat application that behaves almost exactly like Claude or ChatGPT’s web app. Take user messages, send them to the LLM, and display the returned response. You can get some mileage out of playing with your system prompts and adding functionality driven by the user, but the “agent” part comes in when you provide the model with tools that it can call by sending a JSON blob with a tool name and parameters in its responses. For example, you might allow the LLM to list files, make web requests, create git commits, or run your unit tests. You can even give it access to tools created by others via the Model Context Protocol , which I won’t explore in too much depth here. To learn more about tool use, see this article in Claude’s documentation .

Mechanically, the only difference between the typical LLM chat application we’re all familiar with and one with tool use is that you allow the LLM to execute tools, read the responses, and repeat this process in a loop until it decides it has finished with whatever task you gave it (or it hits an error). That’s it. That’s an “agent”. At no point are you required to perform matrix multiplication in your head or chant magical incantations.

Blood sacrifices entirely optional.

My approach #

I decided early on that I was going to be quite strict with the tools I provided. While I have not used any other coding

assistants like smoke, my sense from discussions on X and elsewhere is that they typically allow the LLM to execute

shell commands, possibly with a prompt for the user to approve/deny them, whitelists/blacklists of commands that are

acceptable, etc. This makes the assistants quite flexible, without requiring the creator to write a lot of code. The

LLMs’ training data contains zillions of examples of using common CLI tools, and they’re good at interpreting the

outputs of those tools. But I don’t trust the LLMs enough to give them this kind of unfettered access to my machines,

and my experience auditing the security of “restricted” command-execution-as-a-service in a past life told me I didn’t

want to play this game. So I instead implemented several tools akin to typical Linux coreutils like ls, mkdir,

cat, and grep myself in Go. I also locked down smoke’s access to the file system to a single directory provided by a

flag at runtime.

Well, I mostly implemented these tools myself. Once I had a few under my belt, I could ask smoke to make more for me.

I learned early in my experimentation that the LLMs are quite good at the following pattern: “read the 3 existing

implementations of this interface and create another one named blah that does this.” It really doesn’t take much to

get to this point - just some basic awareness of the directory structure (something like ls), the ability to create

new files, and the ability to write/replace lines in a file. You can knock these basic tools out in a few hours, and

then you’re off to the races.

Having mostly used ChatGPT and Claude to provide relatively short snippets of code to e.g. demonstrate a library I hadn’t used before, or as super-charged “rubber duckies” up to this point, I was skeptical that letting them smash their edits into my codebase directly would produce great results. And indeed, they often miss a curly brace or delete a line they didn’t intend to, to say nothing of the quality of their intended edits. But believe it or not, letting them iteratively write code, run unit tests and linters, check the git diff, write more code, and check it again, will get you code that compiles more often than not.

Is it so over, or are we so back? #

After smoke helped me build itself, I have some new respect for LLMs’ abilities. Different models have different strengths and weaknesses, but on the whole, the well-known models are pretty good (if sometimes ludicrously expensive). I would not let smoke run for 5 hours with vague instructions to “make me an iOS app”. I would not let my mother set it loose on my machine. I would not give it an unlimited credit card budget. But when I decided to migrate this blog to Hugo with a simple custom theme, I reached for smoke immediately. A coding assistant like smoke can handle almost any relatively simple piece of code that you, personally, could implement without making catastrophic errors. But there are some caveats.

At least it’s nice to me 🥲

LLMs’ training data is often woefully out of date relative to the speed of open source library releases. You can try to

cram up-to-date documentation into their context windows, but it’s challenging to give them exactly what they need

without overwhelming them. It was amusing and frustrating to watch smoke insist that sync’s

WaitGroup.Go()

(introduced in Go 1.25) did not exist, and repeatedly offer to help “fix” my code. This

despite the fact that my application still built successfully and its unit tests ran without failures. While I hooked up

the MCP server provided by gopls

, Go’s official language server, the models seemed reluctant to actually use

it without some prodding. LLMs (yes, even the good ones) still hallucinate, though hooking them up to build commands,

unit tests, language servers, etc helps to mitigate this issue somewhat. I’m sure other tools have a better handle on

this than smoke does, so take my impressions with a grain of salt.

When my instructions are quickly carried out to my satisfaction on the first attempt, it feels great. When I have to sit idly twiddling my thumbs while the LLM reads the wrong files, then reads the wrong lines of the right files, then makes its first tentative edit and accidentally elides a required nested curly brace, then seems to pause while pondering the meaning of life before fixing its mistake, I want to scream. For even mildly complicated tasks, I often have to kill the tool-loop and interject some guidance before letting it continue. Sometimes I just go fix the errors in NeoVim myself before continuing. I’m sure this gets better with additional guardrails, shoving more “YOU MUST"s into the context window. The way LLMs evolve code to make it compile or pass the unit tests, though, is just fundamentally different than any human I’ve ever worked with. It’s mostly fine, just different.

Many others have noted that driving an AI assistant is more like project management than traditional software development. While I do enjoy writing, I don’t always enjoy writing a novel just to get roughly the same amount of computer code back, which I then have to carefully read and usually modify. But when it works, man, it works.

Never before in my ~20 years of programming could I have written out in plain English a description of what code I wanted implemented, answered some basic questions, and then gone to make coffee while a machine labored on my behalf to make it so. This feels powerful, and I can understand now why people on X talk about these things like they’re magic. But I also hope I’ve dispelled some of that magic here. Trust me - if I made it, it ain’t magic. The models will (probably) get better, the tooling around them will certainly get better, we will learn best practices for integrating them into our workflows, and programming will never be the same again.

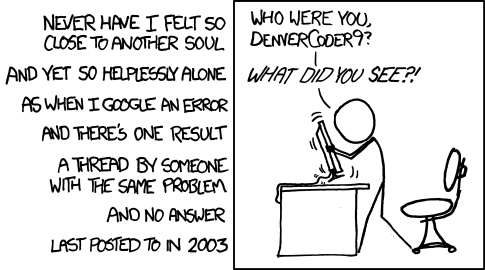

I say this with some sadness, because I actually like programming. Banging my head against some stupid error for what

feels like an eternity. Scouring through crummy documentation and comment-free code to find the name of a method I need.

Spraying a dozen print statements all over the place to track down a bug in some code I could swear I had no hand in

writing. I’ve loved programming ever since I wrote a terrible basic PHP calculator many, many years ago as one of my

first side projects. Figuring out how to make smoke do what I want is not the same as making the code itself do what I

want.

xkcd 979

But sentimentality will get me nowhere. We as developers must adapt to this new reality. While I won’t tell you that you have to make your own version of smoke, I can recommend it as a unique, mostly enjoyable project if you have some free time on your hands. You could certainly save yourself some headaches by using existing assistants to help you build a new one, rather than only relying on the one you’re actively building like I did. The dogfooding was fun, though, and helped me figure out what features I wanted to implement next.

I think we will be using tools like these for some time, though I’m doubtful that they will completely take over all our daily tasks in the short to medium term. Find (or make) the tool you like, get used to its quirks and deficiencies, do what you can to mitigate them, iterate, and try to keep the spark of joy from a freshly green CI job alive.

If people are interested in learning more details about how smoke works, the features I’m proud of, or the ideas I haven’t yet had time to implement, I’ll write a follow-up to this post in the future.

Here’s that link again: https://github.com/cneill/smoke

If you decide to take smoke for a drive, or if you build your own coding assistant, let me know what you learn!